The first years after World War II might be regarded by fashion historians as a period of transition, a period of groping after the lines into which fashion would settle for an 8-year or 10-year span.

The year 1950 could be seen as continuing the transition. Fashion remained deliberately fluid, throwing out feelers in all directions, when they all swing one feelers were cast in the direction of the 1920s, especially by Hardy Amies in London, who showed suits with straight unbelted hip-hugging jackets over straight skirts.

In Paris, too, Dior launched a “vertical line” — sheath dresses whose narrow straightness was emphasized by fine pleating or tucking, or by narrow ribbon bands running from neck to hem. Sheath dresses prevailed for day and evening.

The basis was a figure-fitting sheath, but only in certain instances was this left in a simple, uncompromising form. In general, the narrow line was broken by a jutting sash, a hip bow, an apron skirt, a floating scarf or, for evening, draped complications at hip level.

Another trick for taking the eye off the sheath skirt was the use of transparent fabrics for overskirts and for coats.

Simple tailored coats in chiffon, lace and organdie floated over narrow summer dresses. Loose coats in thin silk were worn over suits, and the prettiest evening coats were those which added no whit of extra warmth but floated with the transparent buoyancy of balloons over narrow or crinoline evening dresses.

Dior dress from Fall/Winter 1950

Although the straight hip-hugging jacket did not seem to make much headway in its extreme form, modified versions of the same feeling were seen in the prevalence of low buttoning and low-placed pockets. Many suits were open to the waist, and buttoned importantly below it. Revers became almost waist-length, leaving a horse-shoe opening over a blouse.

In the spring Dior first showed a dress slim to the knees and then breaking into pleats which developed by the autumn into the full flare of the trumpet skirt. This, in day and evening versions, swung in heavy pleats or stiffened flares, from knee-level, below the simplest of sheaths. When skirts remained narrow, as did the majority, jackets took to flaring out above them from a once-more nipped in waist, and tunics with bell-shaped peplums cut across their pencil straightness at mid-thigh level.

Vertical Changes to Diagonal

In the meantime the vertical look of spring had changed its slant and became a strongly diagonal look by the autumn.

Pleating and tucking, seaming and buttoning, wrap-overs and scarves, all took this diagonal slant. Scarves swelled during 1950 into the proportions of a stole, often a stole so big that it was a wrap in itself. By day, collars had scarf ends that slanted diagonally across the bodice to be pulled through a belt.

Stoles a yard wide and three yards long had their great bulk wrapped around the shoulders of suits, or hung from the neck like jacket fronts, ending in deep pockets.

By night, stoles to match or contrast with the dress fell to the hem, while others ended in fur cuffs or in gloves which held them across the shoulders. The summer’s billowing look of transparent fabrics found solid expression in the most memorable clothes of Balenciaga’s memorable autumn collection, in which taffeta appeared to have been blown up into pumpkin skirts and vegetable-marrow sleeves.

By autumn the box jacket had curved into the short barrel coat, cut away in front. “Little top-coats” became an important fashion feature. Anywhere from hip to 7/8th length, they were more than jackets, less than full-scale coats.

Some were belted and flared in a tunic line; others had a barrel curve; others hung straight almost to the knees; others swung loose. Of the full-length coats, the newest in line were the straight and narrow, sometimes held by a single, off-center buttoning, sometimes double-breasted.

Important double-breasted buttoning was also seen on the skirts as well as the bodices of suits and dresses; altogether there was a great impression of plain tailored buttons being lavishly used on all types of day clothes to emphasize the line.

Fur Makes a Comeback

Fur trimmings were back! But this time with more taste and restraint. Deep fur cuffs would be the only fur touch on a cloth coat; the collar would be small and tailored.

By contrast, a coat with cossack collar in astrakhan would have plain uncuffed sleeves. Fur linings, often showing themselves in turn back revers, bulked “little top-coats.” Linings attracted a great deal of notice to themselves.

The many reversible fabrics demanded a handling that would display both their sides and not only jackets but skirts and sleeves were slit to show contrasting linings; sober coats of black, brown and grey swung open to reveal bright and shiny interiors.

Orange is Back!

In colors, 1950 was chiefly notable for the return of orange after a virtual absence of some 20 years and for the prevalence of white. Small notes of orange had been struck for a season or two previously but early in the year it came out with full force for whole outfits, for hats and for accessory touches.

One of the most difficult of colors for the majority of women, its pinkish tinge, tending towards apricot, was the most popular. For autumn, its influence was felt in a whole range of “hot browns,” the gingers, tans and chestnuts.

In the spring there was a flurry of white in the form of collars, cuffs, gilets, linings. More significant, there were quantities of white coats, white suits, white dresses, pointed up with black accessories instead of the customary reverse proceeding. A white linen suit became the smartest wear for Henley or Wimbledon; a white silk or coarse lace dress for Ascot; and not only debutantes but their mothers wore white ball dresses.

Blues were strongly in evidence, especially turquoise and the mauve-blues, shading into lavender and purple. The grey-beige-oatmeal neutrals held their ground throughout the summer; and the favorite strong color notes were red (from orange to crimson) and yellow.

Velvet won the winter honors: velvet collars and cuffs, velvet blouses and waistcoats, velvet trumpet flares on skirts, velvet accessories, and entire velvet suits and dresses.

Hats remained small, except for a sudden crop of wide-brimmed hats which came out with formal summer dresses. After seasons of sitting on the backs of heads, hats began to move forward and the gap left at the nape was filled by rather longer, softer hair styles and especially by chignons.

In make-up, the heightened naturalness of warm skin tone and clear red lips began to give place, late in the year, to an all-over creamy pallor, with dark red lips the only accent, another echo-with-a-difference of the scarlet-lipped white mask of the ‘twenties.

Many evening shoes consisted of little except soles, high heels, and the thinnest of straps though covered, pointed toes began to be seen.

In costume jewelry, rhinestones invaded the field so long occupied by pearls, slave bracelets set off the arms left frequently sleeveless by blouses and day dresses, and huge cabochon brooches of jewel-colored, single-toned stones were worn on caps and on cuffs, as well as more conventionally.

Captain Edward Molyneux, long famous for the elegant simplicity of his clothes, retired from fashion designing because of ill health.

Men’s Fashion

The 1950 Edwardian Style for Men

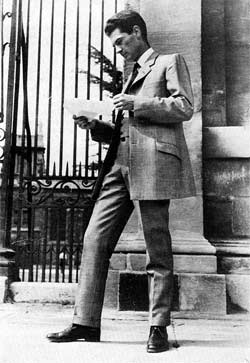

In 1950 there was a return to almost Edwardian formality in men’s clothes.

In suits, the style veered sharply from the full, built-up models of the immediate postwar era to garments which followed the natural line.

Jackets were longer and were made to fit the shoulders, instead of being padded into an artificial line; the lapels became narrower and the trousers took on a tapering look with less width at the bottoms. Several style leaders decided to dispense with trouser turn-ups altogether.

The vogue for single-breasted jackets revived interest in waistcoats, which, in three-piece suits, were cut high and often had narrow lapels. Contrasting-colored waistcoats with brass or leather buttons were increasingly worn with business suits.

The single-breasted trend was also seen in overcoats, which became shorter and were often adorned with velvet cuffs and collars. More somber colors, such as dark grey and black, were favored.

1950 marked the centenary of the bowler hat, which was originally made at the instigation of William Coke of Norfolk who, irritated by the top hat because it caught in trees when worn for hunting, thought a small, hard, round hat would be more serviceable.

The centenary year saw a big revival of bowler hat wearing for business, which, with the tightly rolled umbrella and leather shoes, was a further indication of the trend back to formality. The general tendency towards neatness was further reflected in shirts, socks and ties. In shirts, neat stripe effects returned to favor and these were worn with high, stiff white collars.

In sports clothes, however, brighter, easy-fitting styles predominated but the tendency was towards neatness, not sloppiness. Sports suits in new shades of gaberdine and hopsack weaves took the place of grey flannel trousers and tweed sports coat and lightweight caps became increasingly popular.

For evening wear, the tail-coat came back into its own for more formal occasions, while both single- and double-breasted dinner jackets were seen in a variety of new styles. The popularity of evening wear was enhanced by the introduction of utility dinner suits.

I remember 1957…my first job out of school, Parsons…as a fashion illutrator for Russek’s 5th Avenue. I was one of the first to illustrate “the chemise” and it ran, one single fashion illustration, full page in the Sunday New York Times. The store would soon go belly-up; I had no idea that I was part of the last gasp of survival via eye catching advertising.

I wasn’t born yet but something about that era fills me with nostalgia.